Since 2013, the Berlin-Weißensee Art University has continuously run projects addressing the situation of refugees and displaced people in Berlin. From the very beginning, the focus was on how refugees could contribute their knowledge and skills to the university: the project kommen und bleiben encouraged refugees to give lectures. Whether it was about Arabic calligraphy or Persian carpet weaving, the events were met with great enthusiasm.

When an office building on Bühringstraße, right next to the university, was converted into a refugee accommodation, the question of how to open the university to refugees gained immediate urgency. Not only metaphorically: none of the new neighbors stepped over the university’s threshold. Although the glass entrance hall offers a view of the courtyard with its pear trees and students lounging on the grass, not a single refugee came inside. The welcoming gesture of the transparent architecture—the postwar modernism of the Bosnian Bauhaus architect Selman Selmanagic from 1956—was apparently not enough to make it truly inviting.

Behind the art university, between the refugee accommodation and office buildings, lay a space that, at first glance, seemed far less inviting: a fallow lot, green in spring, parched in late summer, crisscrossed with informal paths. A few years earlier, the university had attempted to establish a garden here with dye plants. Growing vegetables and fruit was prohibited—the soil was considered contaminated. A chocolate factory had once stood here.

In spring 2015, we began transforming the wasteland into a garden. It is still not an idyllic place like the orchard-filled courtyard of the university, but it is an open space. Without fences and, above all, with plenty of room for creativity. It is now used by students, refugees, and employees from nearby offices. We call it bermudagarten, a community garden.

At first glance, the bermudagarten is no different from other community gardens. At its center stands a bright red construction trailer, serving as both a meeting point and workspace. In front of it, under a large canopy, a long table invites communal meals. Around it, raised beds made from pallets and a simple greenhouse. Everything is driven more by experimentation and passion than capital, similar to other parts of Berlin. What distinguishes this garden, however, is the way it fosters interaction with refugees and local residents.

Drawing

Before we even dug a single hole or signed a usage agreement, we drew on the relatively flat part of the lot with chalk powder on the grass: a large rectangle, a line through the middle, a circle at the center, and two smaller rectangles at the short sides. In each stood two frames made from slats we found on the lot. Morning passersby—dog walkers—saw what they expected from the university: art students. The refugees looking out from the accommodation saw a football field. By the afternoon, the first game began, with mixed teams and cheering in German, Arabic, Swedish, and Albanian.

Conclusion: drawing eleven lines and a circle can be a social animation. It also provided a scale for the economy of our design resources.

Trading

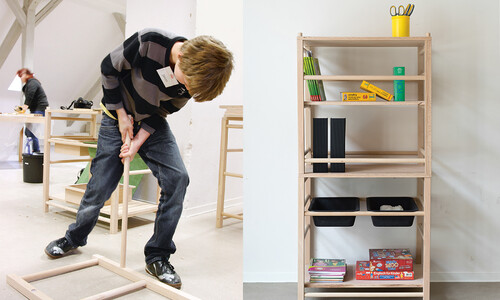

In the following weeks, active construction unfolded on the lot. We brought in topsoil and lumber, built raised beds, planted seedlings, and began fitting out the newly acquired trailer. Always present was a group of children and a team of Syrian, Iraqi, and Albanian men who worked alongside us. Women observed from a distance.

A major topic at that time was fundraising. We decided against donations. Donations create a stark divide between those who give generously and those who need help. Donations imply inequality.

Instead, we organized a swap market in the garden for refugees, students, and neighbors. People could bring items to exchange: a read comic for a pair of red heels, a fur hat for a stroller. Young Syrian and Albanian women examined the offered clothing. Men mostly watched from a distance but were occasionally called over: “Could these pants fit?” The children turned the market into a costume party.

Conclusion: we disrupted the routine of donations. By changing the rules, we could overcome the usual roles—locals give, refugees receive. Breaking gender roles proved harder: none of the refugee women handled a cordless drill. But their men now let product designers show them how to use it correctly. Progress.

Translating

At the end of our first garden year, an unusual request came: could we help a group of refugees—mainly from West Africa and Eritrea—prepare job applications? Resumes with photos detailing their qualifications. Useful when applying for an internship or apprenticeship, or simply to show that they want to integrate into German society.

We underestimated the effort. To produce five resumes in one day required seven students: five to guide the refugees, one to oversee, and one for logistics and tech. Translators helped depending on language, and one or two asylum law experts checked that no phrasing could disadvantage the applicants.

It was challenging. Yet by the end of the workshop, from stories, handwritten notes, and certificates that had traveled in plastic sleeves across the world, nearly twenty resumes were completed. Most importantly: translation—finding the right words. It is not “looked after animals as a child,” but “assisted in family agricultural business.”

Outlook

What we learned during the workshop we documented online. The bermudagarten wiki now contains many instructions. We have fitted out our trailer, host weekly community meals at the university, and founded the association bermudagarten e.V. You can support it or join and participate. From here, our work continues.