Local museums that deal with the history of a small town or village in Germany are called Heimatmuseum or even Heimatstube. Their existence — and the fact that they are open — is often thanks to the initiative of enthusiasts.

Heimatmuseums can show how world events are reflected on a local level: How was common land used? What did the first textile factories mean for the weavers living there? What did the rise of China mean for the local textile industry? How many forced laborers worked here? How many refugees arrived after 1945 — and how many arrive today?

Especially in regions facing strong structural change, Heimatmuseums could be important: for reassurance, encouragement, and the development of new ideas. Unfortunately, they rarely manage to achieve this. Locals visit, if at all, usually only once — why come twice to see what they already know? And why should tourists visit if one Heimatmuseum looks just like the one in the next village? Exhibitions in Heimatmuseums are usually shaped by the joy of collecting — not by strategies of mediation.

We worked with Heimatmuseums and Heimatstuben in the Oderbruch. The Oderbruch is a fertile lowland that stretches about eighty kilometers east of Berlin along the River Oder. It was created in the 18th century when the floodplain was diked by the Prussian state and turned into farmland by economic and religious refugees.

Today the area is experiencing ongoing “structural change,” accompanied by depopulation and an aging population. Still, the Oderbruch is a popular destination for day-trippers from Berlin and for cycling tourists. The cultural offerings are surprisingly rich — in addition to the open-air museum in Altranft and the Oderlandmuseum in Bad Freienwalde, there is a good dozen small and very small museums.

Wollup

One of these Heimatmuseums is located on the land of the former royal-Prussian estate of Wollup, around ninety kilometers east of Berlin. It was founded in 1996 on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of Wollup’s first mention. At that time and still today, the exhibition is looked after by Ruth Schwetschke — on a voluntary basis. She has lived in Wollup since the 1930s.

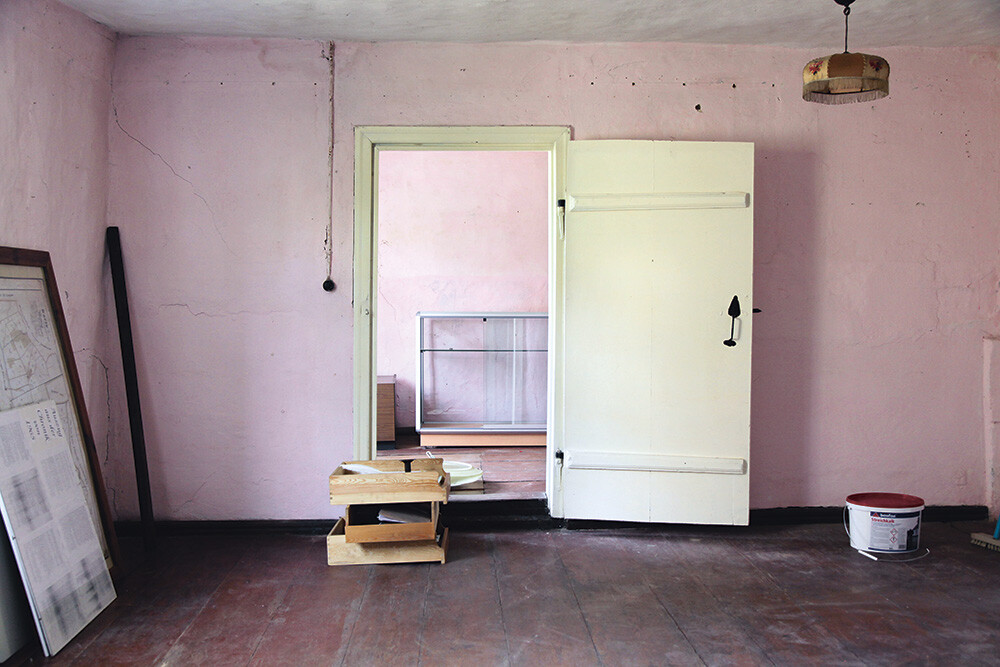

Most of the collected artifacts are shown on the three floors of a storage building. Another part of the Heimatmuseum is located in the gardener’s house at the edge of the manor park. The half-timbered building from 1838 is the oldest preserved farm worker’s house in Wollup and illustrates the living conditions of this social class at the beginning of the 19th century. There are no regular opening hours. Visitors are received by Mrs. Schwetschke on request and by prior arrangement.

Process

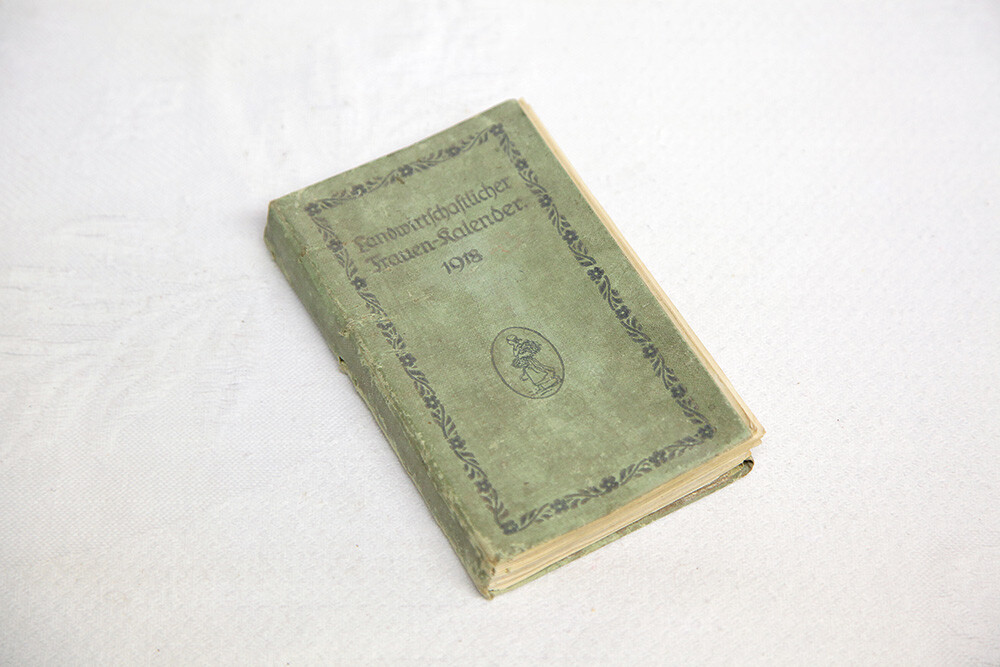

To create an exhibition design that is understood, accepted, and implemented by everyone involved, a 360° perspective is necessary. It is about making the best use of local conditions to ensure the scalability of a proposal. Factors such as the spatial situation, available infrastructure, location, and staffing play an important role. By first working on the renovation of the gardener’s house, we quickly gained a realistic picture of the possibilities and limitations of the exhibition space. We found that due to the high humidity in the house and the inadequate electrical wiring, only an analog exhibition design could be considered. After that, we focused on the existing collection. Detailed conversations with the people of Wollup — over coffee, cake, grilled vegetables, and homemade blackberry schnapps — showed that the objects in the collection only come to life through personal stories. We needed a design that integrated the voices of the people of Wollup into the exhibition. Together we defined time periods and themes that we understood as cornerstones of local history. Each of these cornerstones was to be described with one — only one — object from the collection. We encouraged the people of Wollup to choose such objects and tell a story connected to them.

Solution

We understand the Heimatmuseums of the Oderbruch as parts of a decentralized museum. Some museums already have a clear profile — like the basketry museum in Buschdorf. Others, like the Heimatstube Wollup, still need to develop one. In Wollup, the focus will be on the development of industrial agriculture and its social consequences. The exhibition will therefore also refer to the museum in Möglin, which is dedicated to the agricultural reformer Albrecht Daniel Thaer.

Through profiling and linking, a kind of “museum hopping” can become possible — an attractive offer for tourists. A guidance system must be developed in the region to make the museums visible. Even more important, however, is to give locals a reason to visit Heimatmuseums regularly. Special exhibitions could be such a reason. The smallest museums of the Oderbruch — like the Fontane House in Schiffmühle or the Heimatmuseum in Neulewin — each have two rooms (about fifteen to twenty square meters) and two small chambers (about eight to ten square meters). It would therefore make sense to use one room for changing special exhibitions.

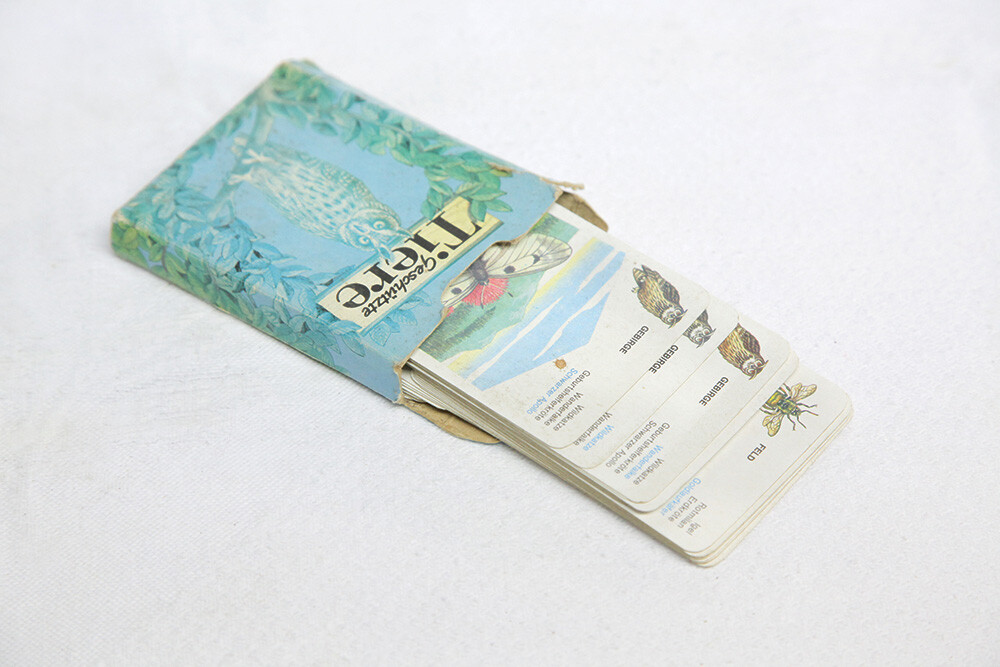

But where should the objects that were originally displayed there go? Most Heimatstuben show an overwhelming abundance of historical household items. But twenty flat irons are not suitable for explaining the social reality of the Oderbruch. Even as an aesthetic experience they are hard to perceive next to twenty sauerkraut pots and twenty beet spades. We therefore propose establishing a central depot in the museum in Altranft. There the artifacts can be stored and researched under optimal conditions. They would be available for exhibitions in Altranft or special exhibitions in the Heimatmuseums.

Design

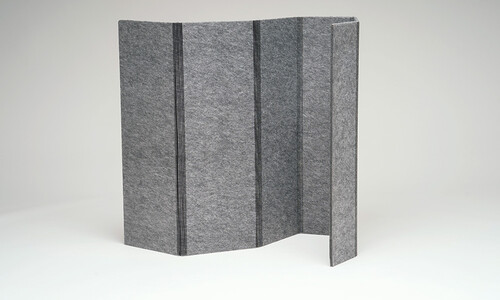

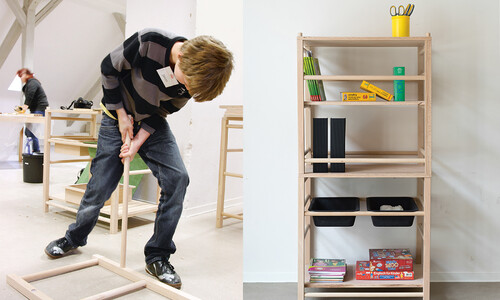

If we want to design the Heimatmuseums of the Oderbruch as part of a networked museum and keep the exhibitions in motion, we need an exhibition system that is suitable for this. It must be easy for one person to move and arrange it.

We developed a system of simple cubes. They are made of square steel tubing — a cheap and robust material. It is non-flammable, flexible, has a neutral appearance and allows for many exhibition layouts. In the Oderbruch, where time and labor are plentiful, there would even be the possibility of having them built by skilled local volunteers.

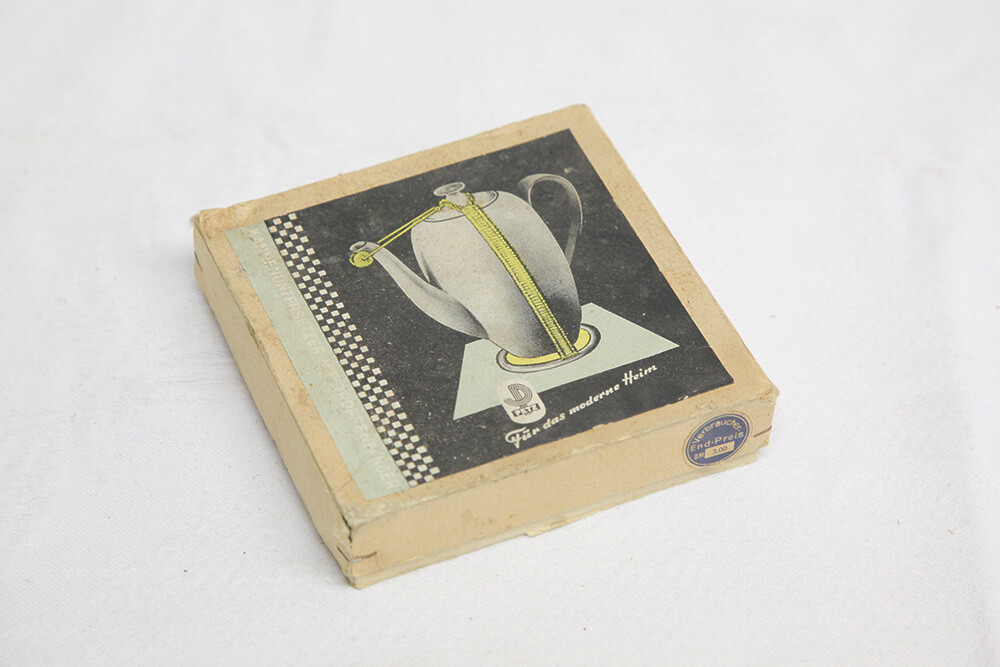

Two to three cubes form one exhibition module. One historical object is shown in each module. It is contextualized with two texts. One text is a story told by a resident of the village — in their own words — in which the object plays a role. This way, a pair of ice skates can tell us something about the relationship between the “lords of the manor” and the workers’ children. Or a coffee grinder can illustrate the hardship after 1945. A second text explains the historical context — for example, the end of the war in 1945 and why most mills in the Oderbruch were destroyed.

This way, starting from concrete objects, we create a dense, local narrative that can be expanded at any time or rearranged for special exhibitions. The story of the coffee grinder, for example, could appear in many different exhibitions — one about the end of the war, or one about “colonial goods” such as tea, coffee, and tobacco.

Implementation

At the beginning of September 2015, we implemented our design in the Heimatstube Wollup and opened it during the village’s annual park festival. As a prototype, it was also presented in the museum in Altranft. The design is suitable for telling interesting history with the existing collections and with the people on site — especially in the Oderbruch, directly on the German-Polish border. It will not remain without contradiction — because the term “Heimatstube” is probably too narrow for a museum that opens up in this way.